THE GARDEN OF THE PHOENIX

Jackson Park | Chicago

CELEBRATING 130 YEARS

1893-2023

The Garden of the Phoenix was established on March 31, 1893 by the United States and Japan as a symbol of their friendship, and as a permanent place for visitors to learn about Japan and experience Japanese culture.

130 YEAR HISTORY

Over the past 130 years, the Garden of the Phoenix has endured through the highs and lows of the U.S.-Japan relationship, and today is one of the most important sites in the nation reflecting the enduring importance of these two country’s relationship.

<- TIMELINE ->

-

![]()

1853-54 | The Opening of Japan by the United States and rapid modernization

Until 1853, Japan had maintained a centuries-old policy of self-imposed isolation from the world. After its shores were forced open by the United States, Japan began to take bold steps to replace its weak feudal government, and rapidly adopted Western science, technologies, and social systems.

By the time of the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, Japan was ready to demonstrate to the world how far it had progressed in only 40 years, and prepared the largest budget and the most elaborate plans of any foreign nation participating at the exposition in Chicago.

Japan’s primary goals were to establish itself in the eyes of the world as a modern, industrial nation that was open to trade and commerce with other nations, and to overcome the unequal treaties that had been imposed upon it.

Milestones in Japan’s development after opening included the restoration of the Emperor as the nation’s leader in 1868, the adoption of a constitution in 1889. By 1893, Japan was ready to present itself as both a modern and ancient civilization to the world.

-

![]()

1890-92 | Japan desires to build on the Wooded Island - the centerpiece of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago

Nearly every nation participated in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Although everyone understood the importance of making a positive impression in Chicago, perhaps no foreign nation understood this more than Japan.

Beginning in June 1890, shortly after receiving its invitation to participate, Japan organized its resources and began sending leaders to Chicago to negotiate for the best locations for its exhibits.

After securing sufficient space in the main exhibit halls to display the fruits of its rapid modernization, Japan sought a site where it could construct a building that could properly introduce the world to its rich artistic heritage, culture, and traditions.

The Wooded Island, located at the center of the exposition, was the most idyllic site because, for the Japanese, this island resembled the physical characteristics of Japan. It would not only be the perfect natural setting for a traditional Japanese building, but such a location would elevate Japan’s status by being at the center of the grand iconic buildings representing Western civilization.

-

![]()

1892 | Olmsted, Burnham and Chicago accept Japan's offer to build the Phoenix Pavilion

The role of the Wooded Island, as designed by Fredrick Law Olmsted, America’s foremost landscape architect and the chief of the exhibition’s landscape design, was to provide exposition visitors a quiet sylvan setting, unencumbered by buildings, in which to escape the hustle and bustle of the exposition.

In February 1892, following lengthy negotiations between the Japanese and exposition officials, Daniel Burnham, the exhibition’s chief of construction, enthusiastically wrote to Olmsted to explain that the Japanese “propose to do the most exquisitely beautiful things . . . and desire to leave the buildings as a gift to the City of Chicago.” Shortly thereafter, Olmsted agreed , and the Japanese Commission was granted permission to build on two acres at the northern portion of the fifteen-acre Wooded Island, provided that Chicago would maintain the building permanently and properly on its site on the Wooded Island as a symbol of the relationship between the two countries and as a place to experience Japanese culture.

On February 19, 1892, the South Park Commissioners (Chicago Park District) concluded a written agreement with Japan.

-

![]()

1891-92 | The Phoenix Pavilion conceived by Kakuzo Okakura

Kakuzo (Tenshin) Okakura with support from architect Masamichi Kuru designed the Phoenix Pavilion and selected its contents. The goal was to showcase for the first time in America the greatest achievements of Japan’s artistic heritage.

The Phoenix Pavilion was modeled after a noted building called the Hōōdō, or Phoenix Hall, located in Uji, near Kyoto. Built in 1052, the Hōōdō is recognized as one of the most important examples of classical Japanese architecture, and remains a symbol of Japan today.

The Phoenix Pavilion consisted of a central hall with two identical smaller structures situated on each side that were connected by a roofed pergola. The arrangement of the buildings was intended to represent the head and body, and flanking wings, of the Phoenix.

The interior of each building was elaborately decorated to display the distinct style of a significant period of Japanese art and architecture.

Kakuzo, also known as Tenshin Okakura, was a scholar and art critic who defended traditional forms, customs and beliefs. Outside Japan, he is chiefly renowned for The Book of Tea: A Japanese Harmony of Art, Culture, and the Simple Life (1906).

-

![]()

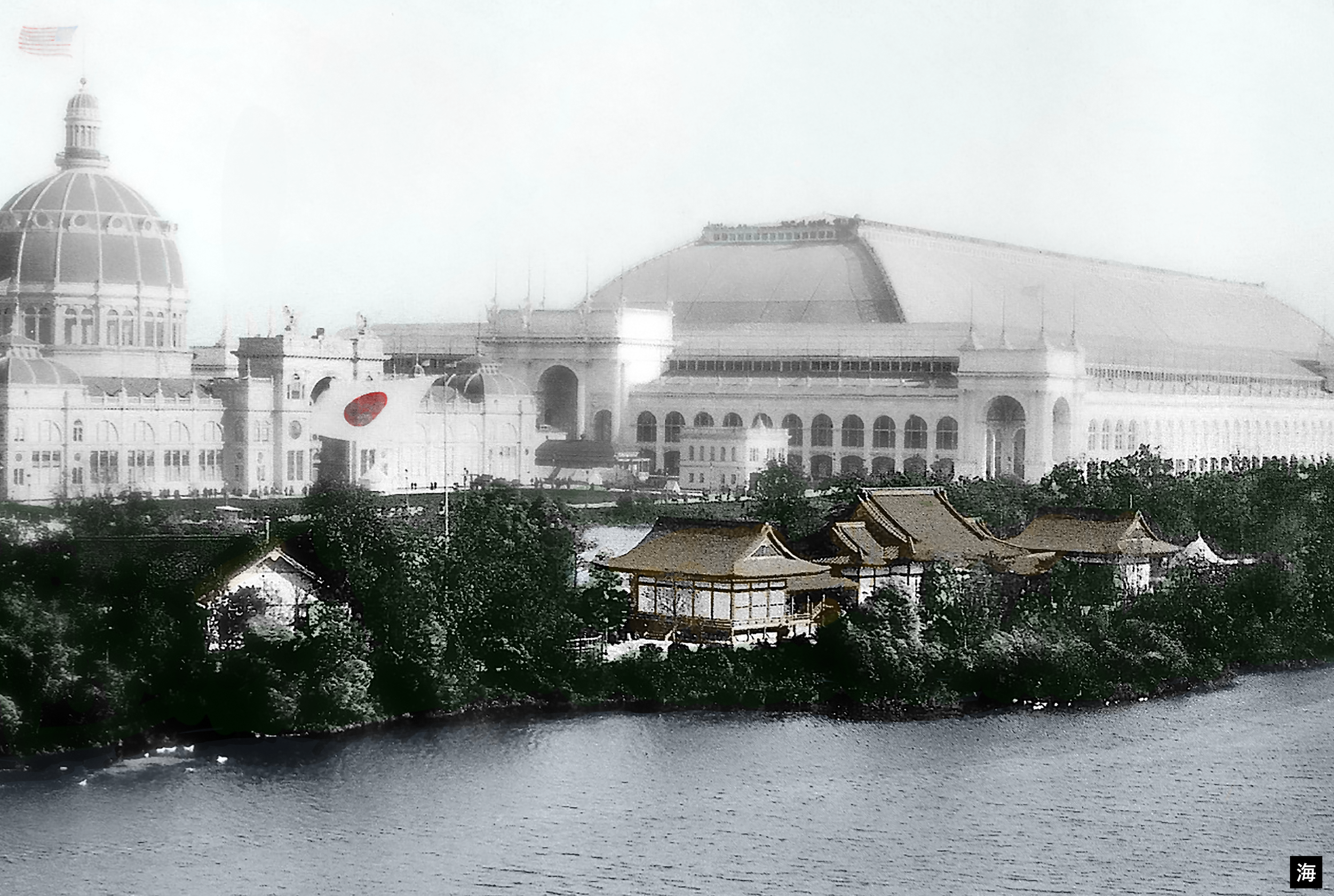

1893 | The Phoenix Pavilion at the center of the World's Columbian Exposition

On March 31, 1893, the United States and Japan dedicated the Ho-o-den (Phoenix Pavilion) on the Wooded Island.

For the millions of visitors that summer, the building—and the canon of Japanese art that it contained—would begin to transform their understanding and appreciation of Japan and its people.

Architects from all over America were fascinated by the Phoenix Pavilion. Foremost among them was Frank Lloyd Wright, who was only twenty-six years old at the time. For Wright, this first encounter with Japanese architecture was a revelation, and led to him experimenting with what he eventually called, “the elimination of the insignificant,” an approach that would lead him to transform American residential design by focusing upon principles inspired by Japan rather than formulas found in the West.

At the close of the Exposition, the Phoenix Pavilion was gifted by the Emperor of Japan to the City of Chicago to serve as a symbol of the relationship between Japan and the United States, and as a place for future generations to continue to learn about Japan and experience Japanese culture.

-

![]()

1904 | Chicago enjoys the Phoenix Pavilion

During the years following the close of the 1893 Exposition, Jackson Park was transformed into a pastoral urban setting for people to connect with nature and each other. As the neo-classical buildings and canals were dismantled and faded into history, a rugged interconnected system of serene lagoons with lushly planted shores, islands, and peninsulas emerged throughout this remote 600 acre (2.4km2) parkland.

The Phoenix soon spread its wings over the Wooded Island to provide a place for Americans to continue to experience Japanese culture, and for nature to flourish.

The Phoenix Pavilion was the responsibility of the South Parks Commission, which managed Jackson Park, Washington Park and the Midway Plaisance. Periodically, government officials from Japan were dispatched to make sure that the Phoenix Pavilion was properly maintained.

Unaccustomed to care required of tatami mats, Japan replaced the mats and instructed the South Park Commission on how to care for the building. Knowledge was passed down though the years and care for the building became a source of pride.

-

![]()

1923 | Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel

From his first encounter with the Phoenix Pavilion in 1893, Wright drew inspiration from Japan. “Japan is the most romantic, artistic, nature inspired country on earth... If [Japan] were to be deducted from my education, I don't know what direction the whole might have taken."

Wright would have the opportunity to repay this debt to Japan when he was commissioned in 1916 to design the new Imperial Hotel, which would become one of the most important buildings in Tokyo from its completion in 1923.

Inspired by the Phoenix Pavilion, Wright created a technical and aesthetic bridge between East and West, and hoped to inspire Japanese architects to create from their soul, rather than imitate the architectural styles of other countries. Being neither entirely Japanese nor completely Western, the hotel was a world in itself - intended as a unique place where people of different cultures could meet on equal terms.

The Imperial Hotel, like the Phoenix Pavilion, influenced generations of architects around the world, including Tadao Ando. “I was overwhelmed by the immense beauty and richness of the space. I was shocked yet intrigued to know that architecture could induce a feeling akin to exploring a whole new world,” Ando explains.

-

![]()

1933 | Japan participates in the Chicago Century of Progress World's Fair

As the twentieth century wore on, the world outside the sanctuary of the Garden of the Phoenix became increasingly complex. By the 1930s, leading nations fell into the throes of the Great Depression, and found themselves on a collision course toward a second world war.

Between 1931 and 1933 tension grew rapidly between Japan and the rest of the world. In February, 1933, just months prior to the opening of the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations over disputes regarding its dominion over Manchuria.

For the World’s Fair, Japan built an exhibit hall, tea house and garden. The tea house, which was of considerable quality, lanterns, stones, and other elements were used after the fair for a new Japanese garden to complement the Phoenix Pavilion in Jackson Park.

-

![]()

1935 | Restored Phoenix Pavilion with new Japanese Garden

On July 27, 1935, the Chicago Park District opened to the public the new Japanese garden, along with the restored Phoenix Pavilion. The new garden included most of the major elements of a traditional Japanese hill-style stroll garden that evolved from the site’s physical conditions, and strived to symbolize a large, natural landscape in a small, concentrated area. In contrast to those Western garden styles that feature lines of trees, symmetrical planting beds, and straight pathways, the stroll garden does not express dominion over nature.

It included a double-pond with islands, a cascading waterfall, stepping stones and a moon bridge. Beautifully carved stone lanterns were placed along the paths to guide visitors throughout the garden. From nearly every vantage point, there were views of distant vistas,

The Phoenix Pavilion and the new Japanese garden became one of the best examples of Japanese architecture and gardens outside of Japan.

-

![]()

1935-1941 | Visitors welcome to the Garden of the Phoenix

The care of the Phoenix Pavilion and its garden was entrusted by the Chicago Park District to Shoji Osato and his wife, Frances Fitzpatrick, who together would operate this site as a Japanese tea garden from 1935 through 1941.

During this brief period, the Phoenix Pavilion and its garden became, arguably, the best examples of their kind outside of Japan. For Shoji and Frances this would become a place where they could escape the mounting challenges that stemmed from their contrasting cultural backgrounds and interracial marriage.

Shoji Osato was born in northern Japan in 1885, and after his parents died, he immigrated to the United States around the turn of the century, seeking a new life and new opportunity.

Following the path from Japan taken by the Phoenix Pavilion, he travelled by ship to San Francisco, and then eventually made his way to Chicago. Along the way, in Omaha, Nebraska, he met and married Frances, the daughter of a prominent architect. Their three children were raised to pursue their own American dreams.

-

![]()

1941 | The Garden closed and Shoji Osato interned after Pearl Harbor attack by Japan

After war broke out between the United States and Japan on December 7, 1941, the Phoenix Pavilion was boarded up and its garden, soon abandoned, fell into decline.

Shoji, like more than 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent, was taken from his family and interned by the government of the only country he now called home.

Despite Shoji’s fate, or in spite of it, his family persevered. Sono, who had left home in 1934 at age fourteen to join the famous Ballet Russe, developed into a national sensation and performed on stage across the country - except in California, where it was illegal for her to enter during the war. In 1945, she stared on Broadway in the controversial casting as Miss Ivy in On the Town.

Teru, their second daughter, married a U.S. naval officer and started a family in Norfolk, Virginia. Timothy, their only son, upon turning eighteen years-old in 1943, joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of the United States Army to fight on the front lines in Europe.

Although the family survived the war, Shoji and Frances’ life in the garden would be no more.

-

![]()

1946 | The Phoenix Pavilion destroyed by arson

In 1946, less than a year after the war ended in the Pacific, vandalism in the garden would lead to arson that would reduce the Phoenix Pavilion to ashes.

Prior to the war, the Japanese and Japanese American population was under 500 people. At the end of the war, over 30,000 Japanese Americans resettled in Chicago after their release from incarceration camps. For these new arrivals to Chicago, the Garden of the Phoenix was unknown or uninteresting, especially in light of anti-Japanese violence and discrimination that they faced upon their arrival.

Following the loss, the Chicago Park District made an effort to maintain the garden and tried to commemorate the lost Phoenix Pavilion with rows of trees and benches. However, with little or no public support, the site was soon forgotten.

In 1950, a proposal was made to convert the entire Wooded Island, including the Japanese garden area, be converted into a zoo.

Over the years, artifacts from the Phoenix Pavilion have been discovered, including four carved wooden architectural transoms (ramma panels) that were created by master Buddhist sculptor Takamara Koun on permanent display at the Art Institute of Chicago.

-

![]()

1946-1980 | The Garden's lost years and the mending of U.S.-Japan relations

When the Pacific War ended in 1945 following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan was occupied by the United States until 1952.

In April 1952, nearly 100 years following the “opening” of Japan by the United States, and 60 years following the arrival of the Phoenix Pavilion, a peace treaty between the two nations came into force and officially ended the war.

With a renewed hope, the two countries would start over on a new path toward peace and prosperity.

In its neglected condition, the island garden that was once graced by the Phoenix Pavilion became overgrown and developed into a refuge for hundreds of varieties of migrating birds. By the early 1970s, conservationists began to embrace the area as an extraordinary wildlife ecosystem, and the island was designated as the Paul Douglas Nature Sanctuary in 1977.

This ecological interest and strengthening ties between the United States and Japan, as evidenced by the new sister-city relationship between Chicago and Osaka forged in 1973, led to the rediscovery of the Japanese garden and interest in its restoration.

-

![]()

1980-81 | Kaneji Domoto designs and builds a new Japanese garden

The restoration of the Japanese garden on the northern end of the Wooded Island was made possible by public and private support.

Kaneji Domoto was commissioned by the Chicago Park District to design the new garden. He based his design on the 1935 garden design with modifications required by the current condition of the site and budget.

Uniquely qualified, Domoto was a landscape architect and architect born in Oakland in 1912, attended UC Berkeley for landscape architecture, and studied with Frank Lloyd Wright. Disrupting his Taliesin education, Domoto was incarcerated with his wife Sally Fujii at Amache, Colorado during World War II. After the war, the Domotos moved to New York and raised four children.

Domoto’s career in architecture and landscape design spanned over 50 years and included several homes at Frank Lloyd Wright's planned community, Usonia. He received many awards for his gardens including the Frederick Law Olmsted Award for his Jackson Park design in Chicago.

-

![]()

1981 | The Japanese garden is reborn

The new Japanese garden was dedicated on June 21, 1981 as a symbol of peace not only between the people of the U.S. and Japan, but all people throughout the world.

With the reestablishment of the Japanese garden, visitors to the Wooded Island could learn about Japan and experience Japanese culture at the site.

In his design, Domoto roughly followed the design of the 1935 garden. On the site of the original tea house, Domoto placed a new wooden pavilion resembling a Noh drama stage. A moon bridge was constructed based upon the design of the original at the outer edge of the garden where the garden pond and lagoon meet. The main gate was modest and placed adjacent to the 1935 kasuga lantern approximately where the original entrance to the garden was located.

-

![]()

1993 | The Osaka Garden

In 1993, in celebration of the twentieth anniversary of Chicago’s sister-city relationship with Osaka, the Japanese garden was renamed the Osaka Japanese Garden.

To deepen its commitment to Chicago, the City of Osaka donated funds for the construction of a new traditional Japanese-style entrance gate designed by Seattle landscape architect, Koichi Kobayashi, and hand-crafted and installed in 1995 by local craftsman, John Okumura.

-

![]()

1997 | Annual Japanese Garden cultural events begin

In 1997, the Summer Japanese Cultural Program was launched with 9 weeks of programming to introduce the public to sumi-e calligraphy, bonsai, kite making, dance, taiko drumming, Japanese garden pruning techniques, martial arts and more.

In 1998, a two-day festival entitled Frank Lloyd Wright + Japan: A Chicago Celebration was added, and included tours, lectures, and a dinner event featuring the combined sounds of jazz and traditional Japanese music led by Tasu Aoki and a tea ceremony led by Urasenke Tea School. During that same summer, a 300 person dinner was held on the site of the lost Phoenix Pavilion to celebrate the 30th Anniversary of Chicago’s sister city relationship with Osaka, Japan.

A 2-day Japanese garden festival continued until 2004, and included children’s activities, a Japanese Bazaar where items were displayed and made available for sale, Japanese food and drinks, taiko drums and koto music, guided tours of the garden and surrounding area, and tea ceremonies.

Sponsors included City of Chicago, Chicago Park District, Friends of the Parks, Consulate General of Japan, City of Osaka, Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, Museum of Science and Industry, Japan America Society of Chicago.

-

![]()

2001-02 | Sadafumi Uchiyama revitalizes Japanese garden and reimagines its future

In 2001-02, the Chicago Park District engaged Sadafumi Uchiyama to complete certain renovations and improvements and develop a concept design for future improvements.

Sadafumi Uchiyama is an accomplished third-generation Japanese landscape gardener, curator of the Portland Japanese Garden., and founder of the North American Japanese Garden Association.

Improvements completed included the elevating the pond above the lagoon, rebuilding of the waterfall, creation of turtle island, and placement of new stone throughout the garden.

Once complete, the cascading water from the waterfall flows into the pond, then down again at the edge of the garden into the lagoon. This improvement was determined foundational to any future improvements to the garden.

Uchiyama’s concept design for future improvements included expanding the garden area and replacing the Domoto pavilion with a functional tea house.

Uchiyama emphasized that in order to cultivate the garden’s future, we must first understand the past. That said, it remained unclear how to treat the area of the lost Phoenix Pavilion.

-

2013 | Sakura to commemorate the 120th Anniversary of the Phoenix Pavilion

In 2013, over 120 cherry trees were planted in around the Garden of the Phoenix to commemorate the 120th anniversary of the Phoenix Pavilion and to celebrate the Garden of the Phoenix as one of the most important American sites that links the past and future of U.S.-Japan relations. Varieties include Yoshino, Gooseberry, Snow Goose, Snow Fountains and Accolade.

In Japan, sakura signify life itself—luminous and beautiful, yet brief and ephemeral. Each spring, people throughout Japan look forward to the blooming of the cherry blossoms, and come together under the trees upon their arrival to celebrate life and renew their spirit. While these moments pass quickly, the hope and progress that they inspire remains.

As future generations visit the Garden of the Phoenix in Jackson Park, we can all hope that they will be inspired to join friends and family under the cherry blossom trees to celebrate life, and remember those people on both sides of the Pacific, like Shoji and Frances Osato, who committed their lives to cultivating peace among nations. As time passes, may these blossoms bloom and the birds continue to sing, so that this hope springs eternal, and together we can create a more peaceful and prosperous future.

-

![]()

2013 | Yoko Ono's first visit to the Garden of the Phoenix and conceives SKYLANDING

In 2013, shortly after her 80th birthday, Yoko Ono was invited to visit the Garden of the Phoenix and the site of the Phoenix Pavilion in Chicago's historic Jackson Park. Ono learned that the Pavilion was a gift from Japan to the people of the United States, and was lost to arson in 1946. Ono returned on many occasions, and there she became inspired to create SKYLANDING.

“Upon my first visit to the site the lost Phoenix Pavilion I felt a powerful sense of place. I reflected upon the history of the pavilion’s creation and its destruction. I felt that this is a special place where we can learn from the past to create a future together.”

A team of architects, fabricators, and other professionals were assembled to work with Ono to complete the project. In addition to the sculpture, the project also included work with musicians, dancers, and a digital team to complete music, performance art, and website.

Born in Tokyo in 1933, Yoko Ono is an artist, poet, musician, and peace activist. Since the early 1960's audience participation and social activism have been crucial aspects of her work.

-

2016 | Obama selects Jackson Park for Presidential Center, and visits Hiroshima and Pearl Harbor

In May, President Obama visited Hiroshima with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of the Pacific War. President Obama’s remarks included: “The world was forever changed here. But today, the children of this city will go through their day in peace. What a precious thing that is. It is worth protecting, and then extending to every child. That is the future we can choose -– a future in which Hiroshima and Nagasaki are known not as the dawn of atomic warfare, but as the start of our own moral awakening. “

In July, President Obama announced his selection of Jackson Park for the Barak Obama Presidential Center (OPC). Construction of the OPC began in August 2021, and is scheduled to be completed and open in 2025.

In December, Prime Minister Abe visited Pearl Harbor together with President Obama. Abe’s remarks including: “I offer my sincere and everlasting condolences to the souls of those who lost their lives here, as well as to the spirits of all the brave men and women whose lives were taken by a war that commenced in this very place, and also to the souls of the countless innocent people who became victims of the war… We must never repeat the horrors of war again.”

-

![]()

2016 | SKYLANDING by Yoko Ono - A Symbol of Peace

After numerous visits to the Garden of the Phoenix in 2013 and 2014, Ono conceived of SKYLANDING - a 12-petal lotus sculpture rising from the ashes of the Phoenix Pavilion representing rebirth, hope and spiritual awakening.

Ono’s intention during its conception was to invite visitors to walk into the center of the lotus and to look within ourselves and realize that peace and harmony begins within each of us.

On June 15, 2015, Ono held a ground healing ceremony and two large mounds were installed to form the shape of yin and yang where the wings of the Phoenix once spread over the land.

On October 17, 2016, a 12-petal lotus sculpture was dedicated at the center of the yin-yang mounds.

This project included the CD-release of SKYLANDING Music of Yoko Ono and the installation at The Art Institute of Chicago of MENDED PETAL, the 13th lotus petal designed by the artist to commemorate the ground healing.

Additional elements for SKYLANDING conceived by the artist are incorporated into the Vision 130.

-

2018-19 | Kazuo Mitsuhashi deployed by Japan to assist with framework plan and improvements

In 2017, the Japanese government decided to support improvements to the Garden of the Phoenix in 2018 in commemoration of as a commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of the start of the reign of Emperor Meiji and his gift of the Phoenix Pavilion in 1893. The Japan Garden Association was entrusted to provide the necessary planning, design and construction support for the development of the garden’s framework plan and to complete a major project to kick-off improvements in advance of the opening of the Obama Presidential Center.

To lead the team, Kazuo Mitsuhashi, a master landscaper in Japan with over 50 years of experience, was appointed and dispatched with a team to work with the Chicago Park District in 2018 and 2019.

Accompanied by Sadafumi Uchiyama, Mitsuhashi visited the Garden of the Phoenix to develop ideas and articulate ideas into a concept design with a portfolio of renderings that would serve future garden planning. Together, along with Karen Szyjga and Michael Dimmitrof of the Chicago Park District, they selected the waterfall as the project to be completed in 2019.

-

2019 | Waterfall project completion

In June 2019, Kazuo Mitsuhashi returned to the Garden of the Phoenix with a hand-picked team of Japanese garden specialists to complete a significant project to commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the start of the Meiji Era. Mitsuhashi decided to complete the waterfall and surrounding landscape as the centerpiece of the Garden of the Phoenix.

The original Japanese garden that opened in 1935 had a small waterfall in the current location. In 1980, Kaneji Domoto reestablished the waterfall with rocks located on the site. Sadafumi Uchiyama developed it further in 2001-02.

For the waterfall, Mitsuhashi selected jagged rocks from Wisconsin that were sculpted from the glaciers that formed the Great Lakes. The rocks and other materials were funded by Michael H. and Suzanne Moskow in appreciation for Mr. Moskow’s having been conferred the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe bestowed the decoration on Mr. Moskow on May 23, 2019, during a ceremony at the Imperial Palace followed by an audience with Emperor Naruhito.

-

![]()

2019 | Peace Day

Master Charles Kim, President of the Chicago Peace School and son of the founder of Peace Day in Chicago in 1978, began this year’s Peace Day in Chicago in Jackson Park, the site of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and where the world came together for the first time as a global community with a shared vision for world peace.

At sunrise, there at the center of Jackson Park, Master Kim visited SKYLANDING to complete Ono’s intention to walk in to the center of the lotus that rises from the ashes of the Phoenix Pavilion destroyed by arson in 1946, and to look inside ourselves and realize that peace and harmony beings within each of us.

There, he mediated and breathed for world peace. Peace Breathing combines the vital energy of breath with the powerful energy of thought to calm your mind, body and spirit and open your heart and find peace within. By attaining peace within, each of us creates strong, peaceful energy which forms the foundation for a broader peace in our families, schools, communities, nations and world.

-

![]()

2021 | Reestablishment of Annual Japanese cultural events in the Garden of the Phoenix

In 2021, a series of events were produced throughout the year by the Chicago Park District in partnership with the Japan Arts Foundation and the Garden of the Phoenix Foundation. The goal is to reestablish annual events to foster a better understanding of the Japanese culture. In 2023, the following events will occur:

HANAMI

KODOMO-NO-HI

OBON

TORO NAGASHI

TSUKIMI

THE FOUNDATION

The Garden of the Phoenix Foundation is a 501(c)3 not-for-profit organization that partners with the Chicago Park District and other organizations to ensure that the 1893 commitment to maintain the Garden of the Phoenix as a permanent and extraordinary place for visitors to learn about Japan and experience Japanese culture is fulfilled now and for generations to come.