Okakura, Wright, Ono and the importance of the Garden of the Phoenix, Jackson Park

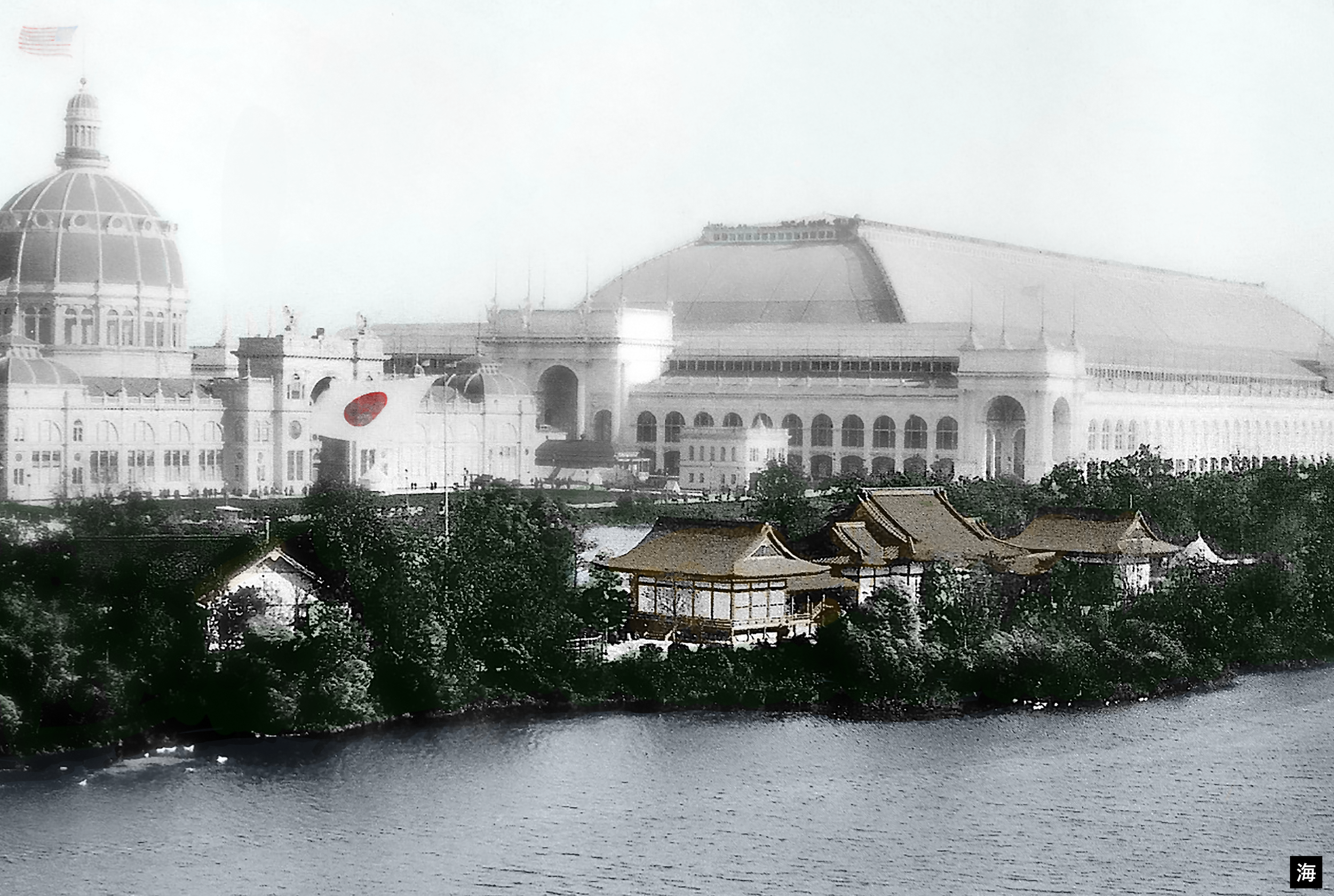

Image: Phoenix Pavilion on the Wooded Island (1893)(Courtesy of Umiimu)

The Japanese have long believed that when a phoenix descends from the heavens, a new era of peace and prosperity will begin.

130 years ago, on March 31, 1893, Japanese and Americans gathered together in the heartland of America, on the Wooded Island in Chicago, to prepare for the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition. They gathered to celebrate the arrival of a Phoenix that would take the form of a pavilion, which they hoped would teach the world about Japan, and, in turn, would lead us to learn about each other and ourselves.

Image: Okakura with Morse, Fenollosa, and Bigelow in Japan (1884) (Courtesy of Umiimu)

KAKUZO OKAKURA and the Phoenix Pavilion

The Phoenix Pavilion was deliberately designed by Kakuzo Okakura with the support of architect Masamichi Kuru to showcase for the first time in America the greatest achievements of Japan’s artistic heritage.

“The United States of America, her neighbor and warm friend, has organized an Exhibition which for magnitude and magnificence exceeds anything the world has ever before seen, and which is accompanied by all those tokens of success that are believed to follow of this great and glorious undertaking.”

“Japan has responded to the wishes of its organizers with joy of the bird as it spreads it wings and carols its song in the heavens. She has come to the Exhibition laden with the treasures of that art which has been the heirloom of her people for the last thousand years.”

- Kakuzo Okakura

Kakuzo, also known as Tenshin Okakura, was a scholar and art critic who defended traditional forms, customs and beliefs. In the 1880’s he worked closely with Ernest Fennolosa to catalogue the canons of Japanese art and architecture, and start a movement to recognize and protect domestic Japanese heritage in an age of rapid modernization. He was a principal founder of the Tokyo University of the Arts or Geidai (芸大), which is the most prestigious art school in Japan. Outside Japan, he is chiefly renowned for The Book of Tea: A Japanese Harmony of Art, Culture, and the Simple Life (1906).

Image: Interior of Main Hall drawing by Kubota Beisen (1893)

For the millions of visitors to the World’s Columbian Exposition, the building - and the canon of Japanese art that it contained - would begin to transform their understanding and appreciation of Japan and its people.

“Never before had the nation been given such a locus for learning about Japan, nor did a building ever have so many meanings and hopes cast upon it.”

- JANICE KATZ, Curator of Japanese Art, The Art Institute of Chicago

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT - Inspired by the Phoenix Pavilion

Architects from all over America were fascinated by the Phoenix Pavilion. Foremost among them was Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), who was only twenty-six years old at the time. For Wright, who would go on to become one of the most important American architects of the twentieth century, this first encounter with Japanese architecture was a revelation.

Image: Phoenix Pavilion Elevation and Floor Plan by Kuru (1892) (Courtesy of Umiimu)

Formed with traditional lightweight timber construction, the Phoenix Pavilion had low eaves and exposed beams, with moveable and removable shoji screens and extensive use of natural light. By using support columns instead of load bearing walls as in the West, the interior space was flexible and open, which created a fluid relationship between the building’s exterior and surrounding natural environment.

For Wright, the Phoenix Pavilion created a unique spiritual and physical order that stood in sharp contrast to traditional European architecture styles which he believed stood out of place on the American landscape. Wright viewed Japan's artistic approach of coordinating the practical and mental requirements of inhabitants with nature as one of Japan’s most valuable contributions to a universal philosophy of architecture.

“Japan is the most romantic, artistic, nature inspired country on earth... If [Japan] were to be deducted from my education, I don't know what direction the whole might have taken."

- FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

Following the 1893 Exposition, Wright' s interest and understanding of Japan and Japanese originality matured as he began to experiment with each building commission to create a new language in domestic architecture that was more sympathetic to its natural surroundings and the needs of its inhabitants.

With the lessons from Japan in mind, Wright began reorganizing the shape and flow of his buildings to develop an individual and original response to each situation, culminating in his first major contribution to the development of American architecture - the Prairie house.

Characterized by dramatic horizontal lines and masses, the Prairie buildings that emerged in the first decade of the twentieth century evoke the expansive Midwestern landscape. The buildings reflect an all-encompassing philosophy that Wright termed “Organic Architecture.” By this Wright meant that architecture should be suited to its environment and be a product of its place, purpose and time.

The Robie House (below), completed in 1910, is one of the best examples of the Prairie house and is located in the Hyde Park neighborhood adjacent to Jackson Park.

Image: Robie House by Wright (Courtesy of Umiimu)

Wright would have the opportunity to repay his debt to Japan when he was commissioned in 1915 to design the new Imperial Hotel, which would become one of the most important buildings in Tokyo from its completion in 1923.

Inspired by the Phoenix Pavilion, Wright created a technical and aesthetic bridge between East and West, and hoped to inspire Japanese architects to create from their soul, rather than imitate the architectural styles of other countries. Being neither entirely Japanese nor completely Western, the hotel was a world in itself - intended as a unique place where people of different cultures could meet on equal terms.

Image: Wright (far left) with team in front of near completed Imperial Hotel (1922)(Courtesy of Umiimu)

“This building – the new Imperial Hotel of Tokyo – is not designed to be a Japanese building: it is an artist’s tribute to Japan, modern and universal in character.”

“The new Imperial Hotel is an offering to Japan in this her time of trial by an artist who owes much to her ancient spirit, one who would contribute his might to repay the debt, hoping to awaken and inspire his Japanese brothers in architecture to independent efforts of their own.”

- FRANK LLYOD WRIGHT

Frank Lloyd Wright profoundly influenced the architecture of the 20th century and left a legacy of proteges who would go on to shape the future of the profession in Japan, such as Antonin Raymond, Arata Endo, and Tadao Ando.

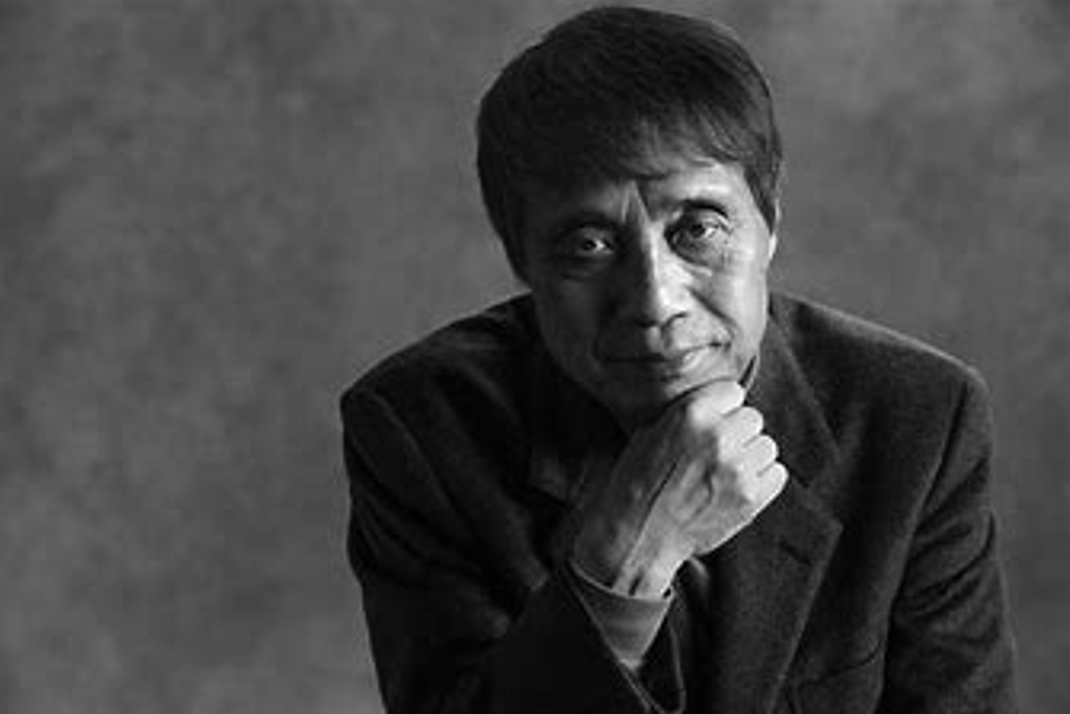

TADAO ANDO - Inspired by the Imperial Hotel

Born in Osaka, Japan, in 1941, Tadao Ando received no formal training in architecture. He started as a boxer, but switched field after being inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. As an architect, he has become a Pritzker Prize-winning architect and one of the most well-known Japanese architects in the world.

Image: Tadao Ando (2019)

Ando was in his late teens when he first saw the Imperial Hotel by Frank Lloyd Wright, at the end of the 1950s. He happened upon the building during a trip to Tokyo. It was well before the beginning of his career as an architect, and he had not yet heard of Wright.

“I was overwhelmed by the immense beauty of Frank Lloyd Wright's space.”

“As I had no knowledge of the technical and cultural complexities of architecture. I was shocked yet intrigued to know that architecture could induce a feeling akin to exploring a whole new world. The building itself was exotic in appearance, covered with local Oya stones and ornately designed fixtures, with a labyrinth-like interior unfamiliar to the canon of Japanese architecture. It was an utterly foreign design which inexplicably integrated with the urban and cultural landscape of Tokyo.”

- TADAO ANDO

Tadao Ando Gallery at The Art Institute of Chicago | First Project in the United States (1992)(Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago)

KULAPAT YANTRASAST - Designing in the Garden of the Phoenix

Like Wright, Ando and his work has inspired countless people around the world to pursue careers in design and architecture. Among them is Kulapat Yantrasast, who grew up in Bangkok, and started his journey to become an architect in sixth grade while making drawings alongside his engineer father. After graduate school at the University of Tokyo, he went to work with Tadao Ando for eight years.

Like Ando, Yantrasast has a penchant for the power of concrete, but he has established a distinct style: decidedly modern, but with openness and warmth.

In 2003, Yantrasast opened his own firm - wHY, and shortly thereafter completed Michigan’s Grand Rapids Art Museum, the first Leed art museum in the world and now credited with bolstering the city’s downtown renewal. Thereafter, many unique and culturally important projects came his way, including the renovation of the Japanese art collection exhibit hall at the Art Institute of Chicago (which includes artifacts from the Phoenix Pavilion), and the 2016 renovation and an addition to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky’s largest and oldest art museum.

Image: Yantrasast developing concepts for New Phoenix Pavilion (2013-15)(Courtesy of Umiimu)

In 2013, Yantrasast and his team were hired by Project 120 Chicago to develop and assist the Chicago Park District with establishing plans for revitalization of Jackson Park, including the establishment of cherry tree groves in and around the Garden of the Phoenix to commemorate the 120th Anniversary of the dedication of the original Phoenix Pavilion.

Work expanded to include concepts for a new Phoenix Pavilion in the historic Music Court in Jackson Park, as well as developing ideas for the space on the Wooded Island where the Phoenix Pavilion once stood until it was destroyed by arson in 1946.

Image: The Phoenix Pavilion destroyed by arson (1946)(Courtesy of Umiimu)

Mindful of the original Phoenix Pavilion’s history and importance in U.S.-Japan relations, Yantrasast and his team of architects and landscape architects designed a new Phoenix Pavilion and its surrounding landscape.

Yantrasast’s graceful and sophisticated design was intended to not only respond appropriately to the site and the needs of visitors to Jackson Park, it reflected and built upon an important architectural and cultural legacy established by the original Phoenix Pavilion.

Images: New Phoenix Pavilion with elevation (Concept)(2013-15)

Image: Site Plan for New Phoenix Pavilion in new location within Jackson Park (Concept)(2013-15)

Image: View from New Phoenix Pavilion toward Museum of Science and Industry and Cherry Trees (Concept)(2013-15)

Image: New Phoenix Pavilion with persevered and enhanced Music Court (Concept)(2013-2015)

The idea for a new Phoenix Pavilion was abandoned in 2016 when Jackson Park was selected to become the location for the Barak Obama Presidential Center, which is now scheduled to be opened in 2025.

Image: President Obama explaining Presidential Center (2017)

Today, Yantrasast and his team, including notable landscape architect, Mark Thomann, continue to work on planning and design for the Garden of the Phoenix and Vision 130.

“My specialty has been what I have termed “acupuncture architecture” - ingenious renovations of existing spaces and context-sensitive additions. The Garden of the Phoenix within Olmsted’s Jackson Park requires such care and attention.”

- KULAPAT YANTRASAST

Image: The Garden of the Phoenix looking north toward the Museum of Science and Industry (Current Conditions)(2023)

YOKO ONO in the Garden of the Phoenix

In 2013, shortly after her 80th birthday, Yoko Ono was invited by Project 120 Chicago to visit the Garden of the Phoenix and the site of the lost Phoenix Pavilion. Ono learned that the Pavilion was a gift from Japan to the people of the United States, and was lost to arson in 1946.

Image: Yoko Ono’s First Visit to the Garden of the Phoenix (2013)(Courtesy of Umiimu)

“Upon my first visit to the site of the lost Phoenix Pavilion I felt a powerful sense of place. I reflected upon the history of the pavilion’s creation and its destruction. I felt that this is a special place where we can learn from the past to create a future together.”

- YOKO ONO

Born in Tokyo in 1933, Yoko Ono is an artist, poet, musician, and peace activist. Since the early 1960's audience participation and social activism have been crucial aspects of her work.

After numerous visits to the Garden of the Phoenix in 2013 and 2014, Ono conceived of SKYLANDING - a 12-petal lotus sculpture rising from the ashes of the Phoenix Pavilion representing rebirth, hope and spiritual awakening.

On June 15, 2015, Ono held a ground healing ceremony and two large mounds were installed to form the shape of yin and yang where the wings of the Phoenix once spread over the land. The next year, on October 17, 2016, a 12-petal lotus sculpture was dedicated at the center of the yin-yang mounds.

Image: Peace breathing in SKYLANDING (Peace Day, 2019)(Courtesy of Umiimu)

Ono’s intention during SKYLANDING’s conception was to invite visitors to walk into the center of the lotus and to look within ourselves and realize that peace and harmony begins within each of us.

With that, Ono brings forward the original intentions of the creators of the Phoenix Pavilion who hoped that this site would inspire us to learn about each other and ourselves.

Video introduction to SKYLANDING by Yoko Ono (2016):